Yeast Cult & Life After Death

- jaymemarsh

- Aug 10, 2018

- 3 min read

Once, in elementary school, to my disgust and dismay, I learned that entire communities of tiny organisms live on my (your) eyelashes. I felt violated. Shouldn’t be all that surprising, considering the tiny organisms that live in my gut, in my mouth, between my toes. Those kinds of living situations are called symbiotic relationships, I learned later. I failed biology in college, had to take it twice, and if there’s one thing I remember, it’s the nature of the relationship I have with the tiny communities that share my body with me.

There’s another community of bacteria that I now share a

space with. They live in an empty preserves jar on top of my refrigerator. Much like a cat or child or plant, we’ve established a regular feeding schedule. That is, I feed them and they, me. I’m a yeast landlord. Once in the morning, and once in the evening, I scoop equal parts flour and water into the jar, give it a stir, and

observe. The jar of sludge bubbles up over the course of a few hours or so, as the bacteria feast, and fart into the jar, creating carbon dioxide and a pungent cherry-soda smell I’ve grown to love. When the time comes, though, I upheave the community, displace their roots into unfamiliar territory, pummel and disorient them, slash their flesh, and relish in their untimely demise, in a scorching hot grave preheated to 500 degrees.

I initially felt uncomfortable about this exchange. I,

the provider of false hope, distracting the yeast community with bread and circuses until I needed something to spread jam on and eat alongside my morning coffee. The evidence of their violent death was beautiful, and left me curious. The golden, blistered crust that whistled quietly when observed fresh out of the oven, something I had grown to treasure about bread-baking, was the result of their final mad dash to escape the dough, to escape death. The bacteria push toward the exit, unsuccessful, and the crust forms because of this.

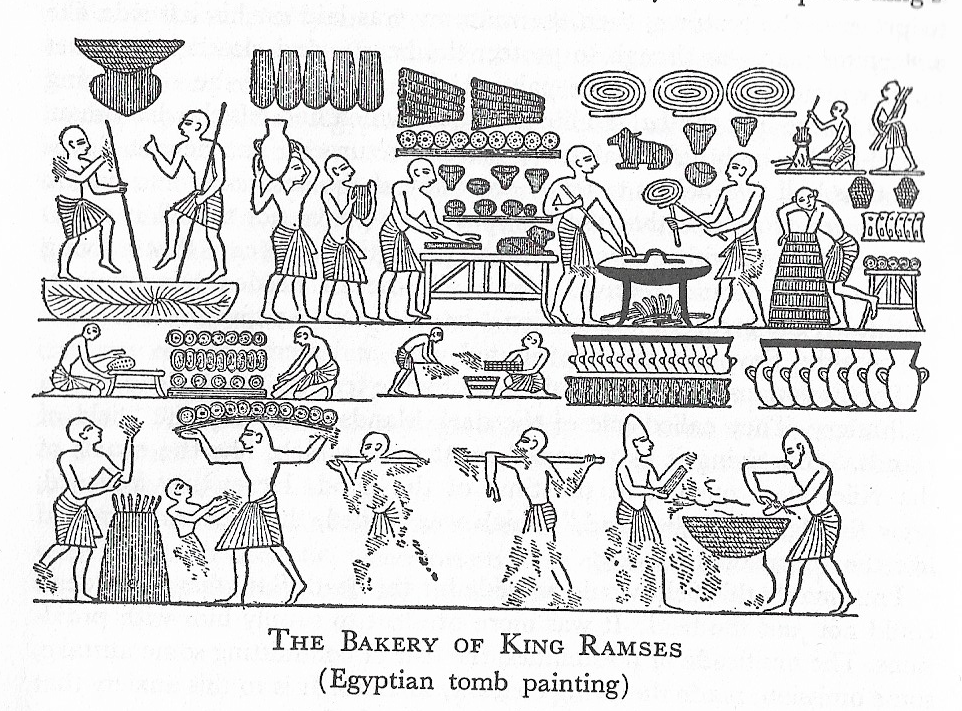

But then I read about the history of bread, of wheat, of baking. The ways it organized communities — communities of yeast, of farmers, of bakers, of civilizations. The religions that formed around it, or in spite of it. The governments that used it to control and dictate their people. I made a list of people I wanted to bake for, with whom I wanted to break bread. I obsessed over recipes and history and technique. And I felt as though my little community of microorganisms hadn’t died in vain.

I watched a documentary recently, which I have since revisited a handful of times, in which a microbiologist nun, Sister Noella Marcellino, discusses her study at the intersection of science and spirituality. She also makes cheese, which ferments with the aid of bacteria much the way sourdough does. She talked about fungi and bacteria and the ways they feast on decay and transform it into something new. Life after death.

When I eat the bread I bake, I’m in dialogue with the bacteria I eat, with the bacteria that eat me. It’s strange that something life-giving, something representative of (or responsible for) life and civilization and culture, for better or for worse, makes me think of my mortality. And what my body might turn into when the time comes.

I’ve just taken a loaf out of the oven, and I think of grandma. Shocker. Her picture hangs in my apartment, next to me, actually, as I write. The ache of missing her has changed over the years, fermented, so to speak. I hear myself offering guests food they don’t want, but that doesn’t stop me. I find myself craving banana pudding with vanilla wafers every now and then. I’ve quit smoking, but walking behind someone and smelling the smoke of their Marlboro Light 100 feels like a wink and a nudge. I bake in my kitchen the way I baked in hers. I hear the whistle of the crust, and it’s time to feed the yeast again.

Sources & additional reading:

1. Six Thousand Years of Bread, by H.E. Jacob (Bakery of King Ramses photo)

2. Michael Pollan's documentary series, Cooked. Episode: "Earth" (Sister Noella Marcellino's cheese)

3. Bread, by Scott Cutler Sherhow (material study and analysis of bread as cultural zeitgeist)

Comments